Authentic Injera (Ethiopian Flatbread)

This post may contain affiliate links. See my disclosure policy.

An authentic Injera recipe, the famous Ethiopian flatbread that’s so perfect for scooping up your favorite Ethiopian dishes and mopping up all of those flavorful juices and sauces. This recipe doesn’t take shortcuts but uses the traditional method for achieving the richest flavor. Whether you choose to use all teff or a combination of flour types, we’ll take you through the process step-by-step to ensure your success!

What is Injera?

If you’ve ever been to an Ethiopian restaurant – certainly if you’ve ever set foot in Ethiopia – you will have heard of injera. It’s a sourdough flatbread unlike any other sourdough. It starts out looking like a crepe but then develops a unique porous and slightly spongy texture. The thin batter is poured onto the cooking surface, traditionally a clay plate over a fire though now more commonly a specialized electric injera stove, and the bottom remains smooth while the top develops lots of pores which makes it ideal for scooping up stews and sauces.

And that’s exactly how injera is used, as an eating utensil. And as a plate. And often in place of the tablecloth. A variety of stews, vegetables and/or salads are placed on a large piece of injera and guests use their right hands to tear portions of the injera which are used for gripping the food. The porous texture of the injera makes it ideal for soaking up the juices.

What is Teff?

Injera is traditionally made out of teff flour, the world’s tiniest grain and also one of the earliest domesticated plants having originated in Ethiopia and Eritrea (where injera is also widely consumed) between 4000 and 1000 BC. Its production is limited to only areas with adequate rainfall though so it’s relatively expensive for most African households. As such, many will replace some of the teff content with other flours like barley or wheat. For those who can afford it, injera made entirely of teff flour has the higher demand.

There are different varieties of teff ranging from white/ivory to red to dark brown. In Ethiopia white is generally preferred and will also produce a 100% teff injera that is a lighter in color than what is shown in the first photo and preparation photos. I’m using 100% dark teff flour which produces a very dark injera with a deeper flavor.

The challenge is that if you’re looking for a specific type of teff and like to grind your own grains, most manufacturers don’t differentiate the teff type on their package labeling. It’s mostly an aesthetic preference though and for most baking I do with teff it really doesn’t matter either way. With the injera it will make a difference in the color though if that’s an important factor to you. On Amazon you can purchase both Ivory Teff and Brown Teff.

Traditionally a clay plate, a mitad, placed over a fire is used for making injera. More commonly now specialized electric injera stoves are used. But unless you’re making injera constantly, a simple non-stick pan on the stovetop will do the job.

A special woven basket, called a mesab, in which the freshly made injera are placed.

What to Serve With Injera

Injera is the traditional accompaniment to Doro Wat, Ethiopia’s famous spicy chicken stew, and together these constitute the national dish of Ethiopia. Injera is likewise commonly served with Sega Wat, the delicious beef version of Doro Wat as well as Misir Wat, a popular vegetarian dish made with red lentils. Injera is a great “neutral” and versatile side to serve with any of your favorite Ethiopian dishes.

Authentic Injera Recipe

Let’s get started!

And I don’t mean short-cut, one-day, cutting corners injera. I mean the real deal – authentic injera.

IMPORTANT NOTE before we begin: Both the texture and color of the injera will vary greatly depending on what kind of teff you use (dark or ivory) and whether or not you’re combining it with other flours. Gluten-based flours (e.g. wheat and barley) will yield a much different texture than 100% teff. In the pictures and recipe below I’m using 100% dark teff, something you will not find in restaurants and will look different than what most are accustomed to, but is traditional to Ethiopian home cooking.

You can buy pre-ground teff flour or grind your own. I like to grind my own grains because 1) the flour has far more nutrition because it’s fresher and the oils haven’t oxidized and 2) I have more control over the texture of the flour.

I use and LOVE my German-made KoMo Classic Grain Mill. It comes with a 15-year warranty. It’s a stone-grinding mill and you can grind grains as finely or as coarsely as you like. It’s an awesome piece of machinery and it’s just downright gorgeous!

Whether you’re grinding your own flour or using pre-ground, you’ll need 2 cups of flour. I’m using all teff flour, and mine happens to be dark teff flour which will produce a very dark injera with a deeper flavor.

As mentioned above, using 100% teff flour is traditionally considered the most desirable (it also happens to be naturally gluten-free), but you can substitute part of it with other flours such as wheat or barley.

However, if you’re new to making injera I recommend substituting a portion of teff with barley or wheat flour as 100% is more challenging to work with.

Stir in 3 cups of distilled water (and the yeast if you’re using it).

I made two versions to show you the difference – both are identical but in one of them I added some commercial yeast (left) and the other one I didn’t (right). What that does is prevent the formation of wild yeast because the commercial, store-bought yeast dominates.

Loosely cover the bowls with plastic wrap so that air can still get in (but no critters can) – cheesecloth is also a great option. Let it sit undisturbed at room temperature for 5 days. You don’t have to let it ferment that long but at least 4 days is ideal and longer it ferments the deeper the flavor will be.

Note: Depending on what kind of flour you’re using, you may need to add a little more water if the mixture is becoming dry.

After 4-5 days both versions will be fizzy when you jiggle the bowl.

Notice the difference between the mixture prepared with commercial yeast (left) and the wild yeast mixture (right). The version made the traditional way allowing wild yeast to form is not only much darker in color, it has a film of aerobic yeast on top that you may initially think is mold but it isn’t. If your batter forms actual mold on it it will need to be discarded.

It looks disgusting, I know. Like why would I eat this? But rest assured it’s perfectly normal. That isn’t mold, it’s aerobic yeast caused by the fermentation process. Going the traditional route of relying on wild yeast – a naturally fermented product – over commercial yeast results in an injera with a richer and more complex flavor. It’s the way injera has been made and enjoyed for centuries. Again though, if your batter forms actual mold on it, it will need to be discarded.

We’re simply going to discard this top layer and use what’s underneath. So pour off the top layer and as much of the liquid as you can.

You’ll be left with a clay-like batter. Give it a good stir.

Bring 1 cup of water to a boil in a small saucepan. Scoop 1/2 cup of the fermented teff batter and stir it into the boiling water until the mixture is thickened. This will happen pretty quickly.

Stir the cooked/thickened batter back into the original mixture.

Add some water to the batter to create roughly the consistency of crepe batter. I added about 2/3 cup of water though this will vary from batch to batch. The batter will have a sweet-soured nutty smell.

Heat a non-stick pan on medium. Depending on how good your non-stick surface is, you may need to very lightly spray it with some oil.

Coat the surface of the pan with a thin layer of injera batter. It should be thicker than making a crepe but not as thick as a pancake.

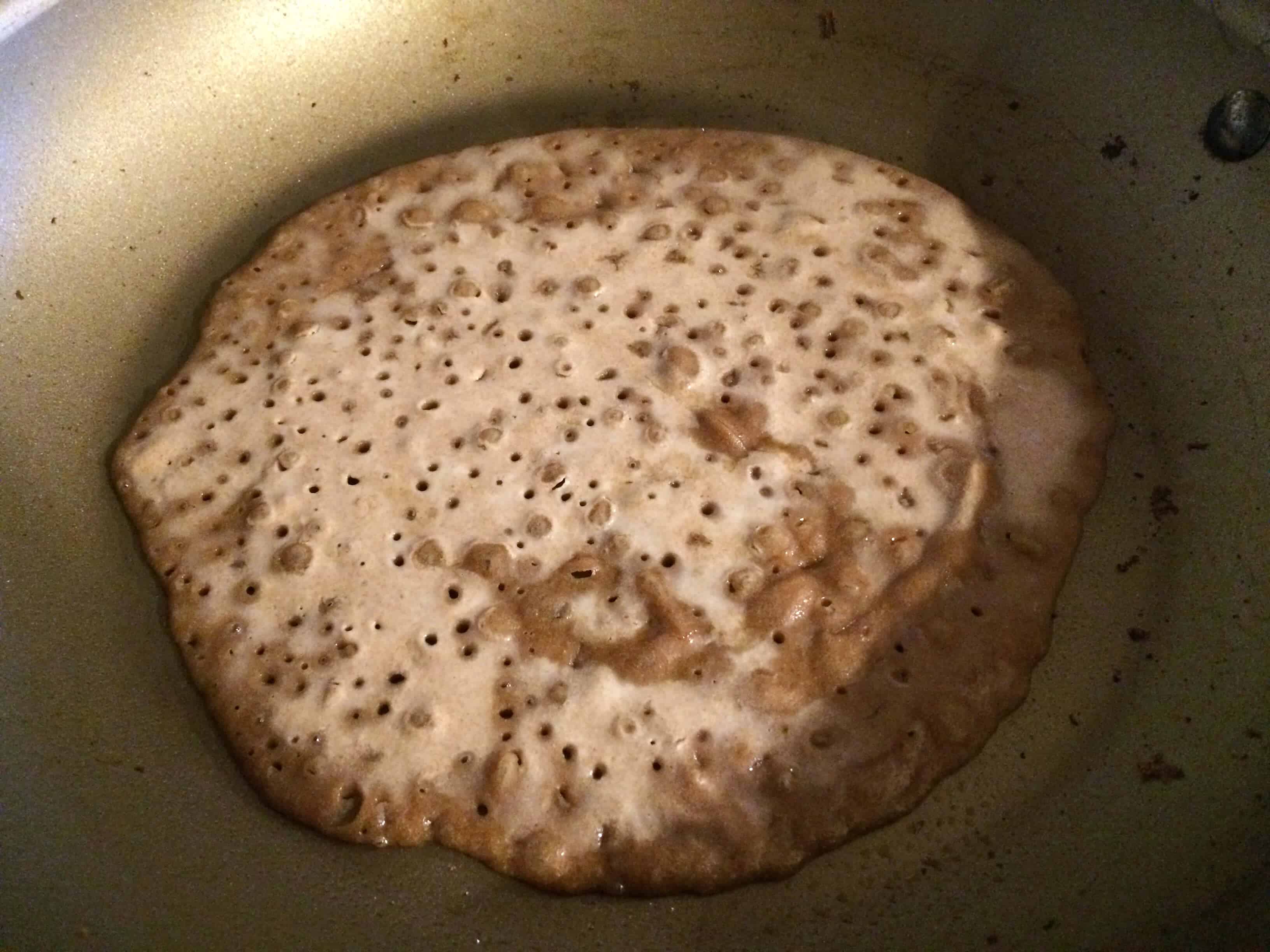

Continue to cook – bubbles will form, allow them to pop. Then cover the pan with a lid and turn off the heat to let it steam cook for a couple more minutes or so until cooked through. Be careful though, if you the injera cooks too long it will become gummy and soggy.

Remove the injera and repeat.

Serve your homemade injera with any of these authentic Ethiopian recipes: Doro Wat, Sega Wat, Misir Wat, and Gomen.

Enjoy!

For more flatbread recipes from around the world to try my:

Save This Recipe

Authentic Injera (Ethiopian Flatbread)

Ingredients

- 2 cups teff flour, brown or ivory , or substitute a portion of it with some barley or wheat flour (note: teff is gluten free)

- Note: If you’re new to making injera I recommend using a combination of teff and barley or wheat as 100% teff is more challenging to work with.

- 3 cups distilled water (fluoride and chlorine will both interfere with the fermentation process)

- Note: This method involves wild yeast fermentation. See blog post for details about using commercial yeast as a starter (you’ll use about 1/4 teaspoon dry active yeast)

Instructions

- *See blog post for detailed instructions*NOTE: Using mostly or all teff (which is the traditional Ethiopian way) will NOT produce the spongy, fluffy injera served in most restaurants which are adapted to the western palate and use mostly wheat, sometimes a little barley, and occasionally a little teff added in.

- In a large mixing bowl, combine the flour and water (and yeast if you're using it). Loosely place some plastic wrap on the bowl (it needs some air circulation, you just want to keep any critters out) and let the mixture sit undisturbed at room temperature for 4-5 days (the longer it ferments, the deeper the flavor). (Depending on what kind of flour you're using, you may need to add a little more water if the mixture is becoming dry.) The mixture will be fizzy, the color will be very dark and, depending on the humidity, a layer of aerobic yeast will have formed on the top. (Aerobic yeast is a normal result of fermentation. If however your batter forms mold on it, it will need to be discarded.) Pour off the aerobic yeast and as much of the liquid as possible. A clay-like batter will remain. Give it a good stir.

- In a small saucepan, bring 1 cup of water to a boil. Stir in 1/2 cup of the injera batter, whisking constantly until it is thickened. This will happen pretty quickly. Then stir the cooked/thickened batter back into the original fermented batter. Add some water to the batter to thin it out to the consistency of crepe batter. I added about 2/3 cup water but this will vary from batch to batch. The batter will have a sweet-soured nutty smell.

- Heat a non-stick skillet over medium heat. Depending on how good your non-stick pan is, you may need to very lightly spray it with some oil. Spread the bottom of the skillet with the injera batter – not as thin as crepes but not as thick as traditional pancakes. Allow the injera to bubble and let the bubbles pop. Once the bubbles have popped, place a lid on top of the pan and turn off the heat. Let the injera steam cook for a couple or so more minutes until cooked through. Be careful not to overcook the injera or they will become gummy and soggy. Remove the injera with a spatula and repeat.

- IMPORTANT NOTE: Both the texture and color of the injera will vary greatly depending on what kind of teff you use (dark or ivory) and whether or not you’re combining it with other flours. Gluten-based flours (e.g. wheat and barley) will yield a much different texture than 100% teff. In the pictures and recipe below I’m using 100% dark teff, something you will not find in restaurants and will look different than what most are accustomed to, but is traditional to Ethiopian home cooking. Make your injera according to what you prefer.

Nutrition

Images of serving platter and woman cooking courtesy Maurice Chédel and Rob Waddington via CC licensing

Originally published on The Daring Gourmet February 7, 2017

Hi, thank you for this awesome guide. My partner uses some of his own sourdough culture as a starter. It works very well. How come you pre-cook some mixture and put in back in? Is that how it is done in Ethiopia and/or Eritrea as well? Thanks so much.

Thanks for the feedback, Keda. Yes, that’s how it’s traditionally done for the purpose of thickening the batter which impacts the texture of the final product.

After making that teff flour n water mixture, did you start making your own sourdough starter, babysit it n save it for future bread making? 😊

I haven’t yet, but need to! :)

I have tried this but I used 2 tbsp of teff sourdough starter when I mixed it before putting it it rest for a few days. The flour sank to the bottom and the liquid on top was really bubbly. It seems to be helpful to clean off the sides with water before putting it to rest so the mouldy top is less likely to form as everything is under the water. I tend to leave mine 3 days as I think that is the taste my family likes best.

Thanks so much. This recipe rocks. It is truly daring to play with real food which actually benefits our bodies. Every day I learn more about making food my medicine and medicine my food. Since I have made many different kinds of pancake-like foods over the years, I knew that it would take some time to figure out the heat on the griddle/frying pan. I found it worked for me to start with a fairly hot griddle and lower it to medium-low. It was surprising to note the heat the teff could tolerate…. many non-wheat flours have to be babied at fairly low temps. It was also surprising how long it took to cook… and that it could continue cooking without scorching. So many pancake like things are lickety-split – in and out of the pan.

Thanks again,

Edith

Wonderful, Edith, and thanks so much for sharing those tips and insights!

I would love to try this, how long does it keep once it’s been cooked? Or can it be stored without going bad?

It’s best served fresh but it will keep for a couple of days in an airtight container in the fridge.

Hi there! I’m a massive fan of Ethiopian food so was excited to find your recipe :) however I really can’t get this bread to work. I’ve got the bubbles going except the bread doesn’t seem to thicken and stays quite mushy. I cooked it on medium heat and then turn it off using the lid on the pan yet it still doesn’t come out right with a rather crisp bottom and mushy top. Any recommendations as to how I could improve this?

Thanks! Xx

Hi Jess, in Step 2 are you pouring off as much liquid as possible? And in Step 3 is the batter thickening up really well? I’m wondering if your batter is too liquidy. Another thing you can try is putting on the lid earlier on to help cook the top.

Thanks for your fast response Kimberly :)

I thought I was but perhaps not!

When I previously tried thickening the mix but then didn’t get any bubbles at all.

All good, I’ll keep trialling and erroring! Thanks for your help x

Hi Kimberly, I’m fascinated to give this a go having fallen for injera two days ago. Have you tried the recipe without the cooking part? You mentioned it improves the texture but I can only imagine this would knock out some of the air bubbles out of it..

Would gently stirring the mixture once/twice a day be advisable to avoid the mold appearing at all? Thanks!

Hi Hugh, I haven’t tried that and all the traditional recipes I’ve seen thicken it first. It will probably be too runny without that step resulting in super thin injera. It’s certainly worth a try though, let us know if you do! The stuff that develops on top of the fermenting batter is known as aerobic yeast, it isn’t mold at all and is perfectly safe – a very natural and expected part of the fermentation process.

Where exactly is the detail regarding using commercial yeast? The recipe says to “see blog post” but the blog post only shows the two bowls, one with commercial yeast and one with wild yeast. If I’m using 2 cups of teff flour and 3 cups of water, how much commercial yeast do I use? Thanks!

Hi Luke, thanks for catching that. You’ll use just about 1/4 teaspoon of it to jumpstart the fermentation process.

Thanks! I’ll have to report back and let you know how this turns out!

Also, do you just add the yeast into the water/flour mixture? Or is there a specific order in which the yeast has to be added? For example, should I let it dissolve in the water first then mix the yeast+water mixture into the flour? Does this even matter? Any information would be appreciated!

Hi Luke, it doesn’t matter – you can just add it in last and give it a little stir in the water.